biography

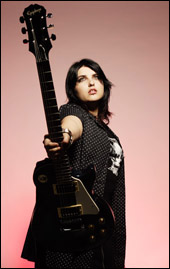

In a world where the pointless, humourless likes of Pete Docherty, a man whose minimal talent is far outweighed by the interest of a media who still insist on glamorising the smack-addled road to destruction they need from a new martyr, it’s heartening to find someone like Vanessa Eve, a young woman who has struggled with the same demons – and a damn sight more – and has come out the other side to allow her creativity to flourish from a now-clear head.

Vanessa, the disarmingly honest and forthright creative force powering Jaed, was born to an Italian father and a Macedonian mother 21 years ago in the quiet Melbourne suburb of Bundoora. For the first five years of her life, she says, she was happy. But then everything started to unravel as her abusive father spiralled out of control, making home life excruciating for her and her mother.

Vanessa, the disarmingly honest and forthright creative force powering Jaed, was born to an Italian father and a Macedonian mother 21 years ago in the quiet Melbourne suburb of Bundoora. For the first five years of her life, she says, she was happy. But then everything started to unravel as her abusive father spiralled out of control, making home life excruciating for her and her mother.

“My dad was a real bastard,” she says bluntly, despite endearingly apologising for the minor swear. “He was really abusive, a big gambler, always having affairs, so there was a lot of fighting and stuff like that. Because of that I started using drugs and playing music. I couldn’t deal with just being at home.”

Her first escape from reality came when her cousin played her Nirvana’s thorny ‘Rape Me’ when she was 12. It opened up a whole new world, encouraging her to learn to play guitar on a toy ukulele before immersing herself in punk rock the day she got an electric guitar of her own. Veruca Salt, L7, Hole, and the Riot Grrl scene became her friends, and she started writing songs of her own a year later. But there was only so much the noise could drown out. So she took a more destructive route to oblivion.

“Because of all the family stuff that was going on it was really traumatic, there was lots of abuse,” she says quietly. “I fell into a really bad depression. It was weird, I was always really curious about heroin. I don’t know why, I just always was. I went up to a girl at school. I knew she smoked pot and would have dealt drugs.”

A few weeks later the two of them were taking heroin every weekend. Then every couple of days. By the time her friend became pregnant and stopped, Vanessa was using it every day, and it was too late for her to back out. By the age of 16, with a habit to feed and a home life she couldn’t stand anymore, she left home and went to live on the streets of Melbourne. She stayed there for four years, digging in with the other gutter punks and junkies.

was using it every day, and it was too late for her to back out. By the age of 16, with a habit to feed and a home life she couldn’t stand anymore, she left home and went to live on the streets of Melbourne. She stayed there for four years, digging in with the other gutter punks and junkies.

“I don’t know why I’m still alive,” she admits. “I really don’t. I just felt invincible, it was weird. It’s only now I look back and think I should have died with some of the things that went on.” The cost of the habit led her into the most obvious way of making cash – she fell into prostitution to make ends meet. It’s a time in her life that’s had a huge impact on Jaed’s debut album – the tales of running around the streets, scoring drugs and making money is both poignant and, sometimes, laced with a wicked black humour that halts self-pity at the door.

While all this was going on, though, the only passion outside of the drug that never faded was that for her music. Even in the darkest days, she kept writing, busking on the streets for change, playing with bands she formed at school with songs influenced by the Breeders, Nirvana and the Pixies. Her big break came, unbelievably, when she was out shoplifting one day.

“Brunswick Street is a really cool street in Melbourne, and there was one shop I used to go into all the time, it was a rockabilly shop,” says Vanessa. “I used to take jeans and shirts and badges all the time. I always used to talk to the guy who owned it, Chris. I think he knew all along, but one day I went in and stuffed some things down my pants and he came out and confronted me. We had a big argument until I gave in. Then we got talking, it was weird, he didn’t hate me. I told him about my bands and about what I was doing. I gave him my demo, he loved it.”

The benevolent shopkeeper arranged for her to meet Barry Palmer, one of  Australia’s top producers. She took him a tape of her songs – furious, punky, and often witty tales of her most unusual life. But when the producer pressed play, there was complete silence coming through the speakers.

Australia’s top producers. She took him a tape of her songs – furious, punky, and often witty tales of her most unusual life. But when the producer pressed play, there was complete silence coming through the speakers.

“He still thinks to this day that there was nothing on the tape, he’s convinced I did it just to get in the door,” she laughs. “But I swear to God it really did have music on it! He still can’t find anything on the tape. So I borrowed a guitar and I played him my stuff and he loved it. I was pretty fucking lucky.”

There’s little wonder he was so impressed, despite his disbelief. The likes of ‘My Way’ (about “the work that I’d done on the street. It’s about that and the hold that heroin had over me. It’s sort of a black humour.”), ‘Gutter Girl’ (a spikey punk affair written in detox), the heartbreaking ‘Scream’ (“about being abused in whatever way by someone you trust…”) and the defiant ‘Someday’ (“It’s just saying ‘fuck you’, and how hard it is not having anyone who has faith in you, just being on your own. You have to believe in yourself because nobody else does. I’ve learnt that I can’t give up. If I’d given up, I’d be dead”) are some of the most rawly personal, honest rock songs you’ll hear all year. But this is far from navel-gazing angst – Jaed’s music rocks like Verruca Salt and Hole before them. And on the flipside of the dark experiences, there are downright funny songs like ‘Catherine’, a 47-second attack on an unloved acquaintance that echoes Blondie’s ‘Rip Her To Shreds’ and has the brilliantly childish line “You think that we’re junkies, but you don’t wash your undies”, or ‘Dream Hair’ having a good laugh at a ridiculously vain boy.

“He was such a pretty boy,” laughs Vanessa. “It was pathetic!”

They’re songs of experience, good and bad, from a girl who hit rock bottom at a very young age, and who has climbed out of the hole she dug for herself with only her own self belief and her own music to spur her on, sense of fun intact.

“I don’t mind being open,” she states, in a typically no-nonsense manner. “There’s some stuff that I do like to keep to myself but I write that stuff because it’s my way of dealing with things, it’s my therapy, my release. If someone else can listen to that and it’s a release to them if they’re going through something similar that’s fucking great. I don’t mind at all.”

There is a happy ending to all this. After 24 attempts to detox she’s now been clean for a year. “I’ve gone from that extreme life to having a full-time job, not using drugs,” she grins, referring to her current occupation as a fence builder. “It’s very new!”

She’s also got her dream line-up together. After parting ways with an original, sub-par bassist and a drummer who, while he was one of the best in Australia, was far too old for the band, she’s got together with a couple of former session musicians from England.

“The line-up now, I’m blessed, they’re amazing,” she beams, glowing with pride. “Matt is an incredible drummer, he’s got so much charisma, and Greg is such a kick-arse bass player They’re really close, they’ve played together their whole lives. You can tell when you watch us that they’ve played together forever.”

On top of that, they’ve signed to indie label Instant Karma / Dharma Records over here – a deliberate move to avoid the major labels and, subsequently, the blanded-out makeover jobs they so often insist on inflicting upon raw and exciting female talent. Clearly, Vanessa Eve is prepared, after all she’s been through, to compromise for no-one. “I didn’t want to sign to a big major label because I will not be manipulated,” she states. “I will not be told what to wear or how to write my songs. It’s good, they let me do my thing.”

Each step is a small one, but Vanessa’s future as a symbol of unrestrained musicianship, survival and a strong, intelligent female voice are already there for all to witness in her debut album.